A FRIEND I BUY seed potatoes with and I were scratching our heads as we filled out the order form, blanking on the line where it said “preferred ship date.” How early do we want them to arrive, we asked ourselves as we do every year. Time for a review of that and other questions about when and how to plant, hill and harvest potatoes. (That’s a row in my raised beds here, seen in late spring one recent year.)

A FRIEND I BUY seed potatoes with and I were scratching our heads as we filled out the order form, blanking on the line where it said “preferred ship date.” How early do we want them to arrive, we asked ourselves as we do every year. Time for a review of that and other questions about when and how to plant, hill and harvest potatoes. (That’s a row in my raised beds here, seen in late spring one recent year.)

Many companies ship extra-early, based on rough frost-date estimates for each area that may not be exactly what’s going on at your place, but is that really when I want the starts to arrive? I asked for advice from Alley Swiss of Filaree Farm, a longtime certified-organic farmer in Okanogan, Washington, whose main crops—garlic, shallots and potatoes—are favorites in my garden, too.

(You might recall the popular garlic-growing Q&A Alley and I did together, and our later garlic-growing piece in my column in “The New York Times.” I’ve learned a lot from our ongoing conversations-including that it’s OK to wait a little while for the seed potatoes to arrive.)

how to grow potatoes, with alley swiss

Q. When is the right time to plant—is there a cue in nature to remind us, or a soil temperature or calendar date we’re looking for?

A. At the earliest, I recommend planting two to three weeks before your average last frost date. Seed potatoes can rot if planted too early in cold water-logged soil. If your potatoes do get a heavy frost after they emerge, they will put up new shoots, but every time they die back they will produce a smaller and later harvest.

I like to wait for the soil to warm up a little at which point they emerge quickly and grow steadily without stress. Late March to early May is a good time to plant potatoes in the northern states. In the warmer areas of the South they can be planted in late fall or early winter.

Where I farm the local point of reference is to plant your potatoes when the snow is almost melted off the mountain. Whether it’s the first dandelions blooming or a particular bug emerging; if you talk to gardeners where you live they will probably have a local reference, too.

Q. Sometimes when seed potatoes arrive, some are nearly a tennis ball and some are mere eggs. Should I cut the larger ones up, and do I have to let them callus before planting if so?

A. Many people choose to cut their larger sized-seed potatoes into pieces. The advantage of doing this is your seed will go further and likely produce a higher overall yield.

If you do choose to cut your larger potatoes, make sure and leave at least two “eyes” for every piece. Use a clean, sharp knife to cut the potato into several large pieces shortly before planting.

Leaving the cut pieces in a cool and humid space overnight will give them enough time to callus before planting. The callus will help prevent infection from soil contact.

We plant our seed potatoes whole to minimize worm damage. If you have problems with wireworms, maggots or other pests, planting whole potatoes may be a good idea. Pests are attracted to the juicy exposed flesh of a cut potato.

Q. I have read so many variations about soil prep for potatoes. Is there something they do want, and anything they don’t? (For instance, I’ve read to avoid using manures on the potato bed.)

A. The ideal soil for growing potatoes is a loose and deep loam that holds moisture and also drains well. Luckily, for those without “ideal” soil, potatoes are hardy and adapt well too many difficult soil types. Lots of organic matter is recommended for the best yields. It is best to incorporate organic matter or compost into the soil in the fall so the soil has time to balance the added nutrients.

Fresh manure can activate the pathogen “scab,” which makes for unsightly, yet still edible, potatoes. For this reason I use only well-composted manure when preparing soil for potatoes. If you do not have access to composted manure, a well-balanced fertilizer can be used (I use an organic 4-2-2). Too much Nitrogen will delay root production and you may end up with huge plants with little potatoes.

Q. So I’m ready to plant, following your above prep guidance. Now what? Proper depth and spacing—and is it the same whether a big baker or a smallish fingerling?

A. Dig a shallow trench about 6-8 inches deep. This can be done with a rake in loose soil, but you may need a shovel or hoe in heavier soils.

Place cut potatoes 10-12 inches apart in the trench. If larger potatoes are planted whole they will produce larger plants and should be given a little extra room, 12-16 inches.

A spacing of 36 inches between rows in adequate but if you have the extra space, further spacing will make hilling easier.

Fingerling and other small potatoes can be planted closer, but no less than 8 inches between plants. Cover the plants with about 3-4 inches of soil, leaving the trench partially filled.

Q. The hilling thing is probably the most confusing part (and the most work). When and how deep and often do I hill, and where is all that extra soil meant to come from? Can I use straw or composted leaf mold or some other “mulch”?

A. Hilling is the most crucial, tiring and fun part of growing potatoes. When your potatoes reach about 8-10 inches high, bring soil up around the vines from both sides. This can be done with a rake in loose soils. If your soil is hard, you may need to cultivate the soil before raking or use a hoe.

A. Hilling is the most crucial, tiring and fun part of growing potatoes. When your potatoes reach about 8-10 inches high, bring soil up around the vines from both sides. This can be done with a rake in loose soils. If your soil is hard, you may need to cultivate the soil before raking or use a hoe.

Make sure not to cultivate too closely to the young plants as to not disturb the new roots systems. Hilling brings loose soil around the vines where the potatoes will form as well as deepening the roots into cooler soil. With the first hilling, I like to cover the vines up so that only the top leaves are exposed. This allows for a shallower second hilling done 2-3 weeks later with an additional 2-4 in of soil brought around the vines.

A mulch that is loose and allows the soil to breath can be applied after, or instead of, a second hilling. I recommend straw [above photo, a second hilling of straw in Margaret’s garden] because it breathes well, but leaves can be used as long as they are not applied too thickly.

A good layer of mulch can help protect vines from potato beetles by creating a barrier as well as providing habitat for insects that eat the beetle’s larvae. The fun part of hilling is looking at your beautifully hilled rows when you are done!

Q. What’s the above-ground signal for when it’s OK to harvest new potatoes? Do all varieties offer this possibility?

Q. What’s the above-ground signal for when it’s OK to harvest new potatoes? Do all varieties offer this possibility?

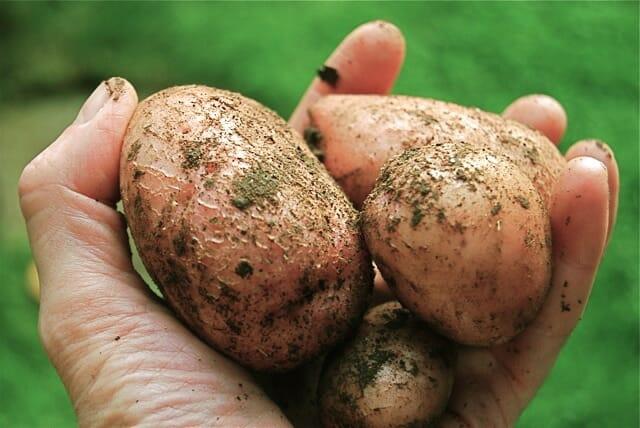

A. Potatoes begin to produce tubers after flowering. Several weeks after flowering, dig into the loose soil at the sides of the vines and you shouldn’t have to dig deep to find thin-skinned new potatoes. These can be pulled from the plant without harming the development of the still maturing potatoes.

The waxier-textured potatoes are best for immature use. The variety ‘All Red’ makes for a colorful new potato with bright red skin and a pink streak through the flesh. ‘Yukon Gold’ is another early maturing variety with great flavor.

Q. How do I know when the crop is done, and how long can I leave them safely in the ground after that?

A. Potatoes are ready to harvest when their vines die back and they lose most of their color. This can occur with a frost or simply when they have reached full maturity.

I like to mow the vines a few weeks before harvest. This helps toughen the skins for good storage.

Potatoes can be left in the ground for several frosts, but should be harvested before the danger of a heavy frost that could damage the spuds lying closest to the surface.

- Browse organic seed potatoes at Filaree Farm

Rolex Milgauss 116400GV Blue Dial

Rolex Milgauss 116400GV Blue Dial