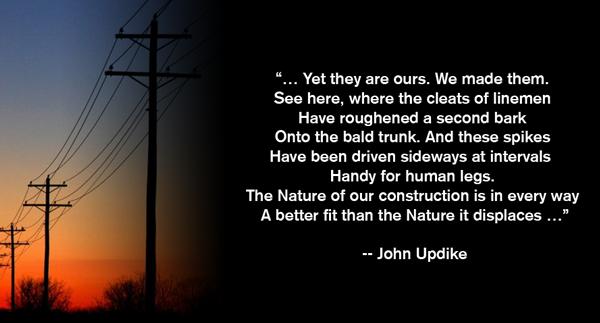

Wood poles have been an essential part of America’s communication and electrical infrastructure for more than a century. With an estimated 150 million poles in place in North America, wood poles have become so ubiquitous that they even inspired poetry.

Wood poles are part of our overall culture because we live in a country blessed with an abundant forest resource. Our ancestors learned early on how to utilize this resource to meet our needs, and the versatility of wood allowed us to adapt it to changing uses.

Even in the technology dominated 21st century, wood poles remain the top choice for utilities. With a long record of performance, competitive, cost-effective pricing and far greater environmental benefits compared to alternatives, wood poles shall continue to bring power to North American homes and businesses for the next century.

History of Wood Poles

The first documented use of wood poles was in 1844 with the development of the telegraph. Samuel Morse received a $30,000 grant from the U.S. Congress to construct a 40-mile telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington D.C. Morse originally tried to put his new telegraph lines underground, but in the first few miles the lines failed. So he turned to placing the lines overhead and advertised to buy 700 “straight and sound” wood poles.

The success with telegraph wires led to the use of poles for wires to distribute electricity. With the development of electricity generation and the need to carry that electricity to homes and factories increased demand for wood poles to carry the wires, insulators and other items required.

By the turn of the century, the need emerged to have standards to create a consistent supply of wood utility poles with predictable structural capabilities. In 1908, standards for round timbers were developed and soon after, the American National Standards Institute, or ANSI, adopted standards specifically for wood utility poles, defining the sizes and characteristics allowed.

Over the same time, standards for pressure treating wood with preservatives to extend their service life were developed through the American Wood Protection Association, or AWPA. In Canada, the treating standards are administered through the Canadian Standards Association, or CSA.

Over the next eight decades, the wood utility pole became an essential part of the North American electrical infrastructure, with an estimated 150 million poles in place. Wood poles have achieved a long record of in-place performance where the service life has been extended to 70 years or more.

Through research, testing and development of new technologies, we’ve learned more about the structural capabilities of poles and that is reflected in today’s standards. In the U.S., the specifications for wood poles, including manufacturing, class dimensions, quality of work and finishing, marking, handling, storage and inspection, are detailed in standard ANSI O5.1. In Canada, wood pole specifications are published in CSA Standard O15-15, Wood Utility Poles and Reinforcing Studs.

Making Wood Poles

Longevity and durability are essential requirements for utility poles. As a natural material, wood poles exposed to the outdoors face significant threats from predators such as mold, decay fungi and insects like termites and wood borers. These organisms seek to break down the wood fiber, reducing the structural soundness and serviceability of the wood.

Preservative treating creates a chemical barrier that protects wood poles from these threats, allowing them to remain in service for decades.

The preservatives are not just on the surface, they are infused deep into the wood to provide long-lasting protection. As a result, the service life of a wood pole can be extended to as long as 70 years or more.

The treating process utilizes pressure that forces the preservatives into the wood fiber. While there are a variety of preservatives used today, the manufacturing process is virtually the same for all.

Into the Forest

Getting the best pole starts in the woods. Poles are typically made from three species: Douglas Fir, Western Red Cedar and Southern Pine. Logs that have the potential to become wood poles are selected in the forest, often while the trees are still standing.

Trees are judged for length, straightness, taper and other characteristics that may impact the load-carrying abilities. In a typical stand of timber, only 7 percent of the trees have the qualities needed to make a utility pole. They are then harvested and transported to manufacturing with trailers specifically designed to accommodate the longer timber.

Once at the yard, the bark is removed from the full length of the tree and the pole is shaped to make it straight as possible. Each pole is reviewed, graded and assigned a class as defined in the ANSI standards. The characteristics reviewed include grain orientation, presence of decay, knots and splits.

Next, the poles may be incised, bored or conditioned to prepare the wood to receive the preservative. Other holes for hardware on the pole are bored, maintaining the protective envelope by allowing treatment to penetrate all openings. Each pole is then branded and tagged, then stacked for treating.

Preparing the Pole

To ready wood poles for treating, they must be seasoned or conditioned in a way that maintains strength characteristics. Poles may be air and kiln dried, similar to what is done in drying lumber. Poles may also be steamed or Boultonized in a long pressurized cylinder, also called a retort.

Steaming is mostly used for Southern Pine poles, however Douglas Fir poles treated with water-borne preservatives also may be steamed. Douglas Fir is typically Boultonized, where the retort is pressurized and the preservative is heated to 180 degrees to 220 degrees F. ANSI standards also require sterilization, specified as heating the pole to reach at least 150 degrees F at the center of the pole for at least an hour.

Infusing the Preservatives

The preserving process begins after poles are loaded onto carts and moved into a retort, which can be as long as 130 feet. Depending on treatment type, air pressure or a vacuum is applied. The retort is then prepared to be filled with preservatives that will be infused into the wood fiber.

Five preservatives used today for wood poles: Pentachlorophenol (Penta), Chromated Copper Arsenate (CCA), Copper Naphthenate (CuN), Creosote and Ammoniacal Copper Zinc Arsenate (ACZA or Chemonite). Each of these preservatives are approved and regulated by the EPA. See the Preservatives section for more information.

The preservative solution is pumped from storage tanks, completely filling the retort. Pressure is continuously applied within the retort to force the preservative into the cells of the wood. The time the poles are in the retort will depend on the size, species, preservative and other factors.

At the end of the treating process. the retort is emptied of preservatives, which are pumped back into tanks to be used again. The treated poles emerge onto a drip pad where excess preservative is captured.

Quality Control

Representative core samples are taken from the poles and analyzed to ensure that quality and durability standards are met. Third-party inspection agencies also take core samples during regular visits to confirm the plant’s quality control practices.

The finished preserved wood poles are then moved to a sorting yard, where they can be shipped to utilities for immediate placement into service.